Kazakhstan is generally not considered to be at particularly high risk of natural disasters compared to many other countries. However, due to the vastness of its territory, harsh climate, changing demographics, and socio-political background, the country does face some significant natural hazards as well as challenges in mitigating them. According to UNICEF, 75% of the Kazakhstan territory is subject to a risk of natural disasters, such as hurricanes, landslides, mudflows, floods, epidemics, extreme temperatures, earthquakes, forest and steppe fires [UNICEF, 2017]. In recent times, the severity and frequency of different types of natural disasters in the country have notably increased. Thus, Kazakhstan was hit by severe flooding in the Spring of 2024. From late March to early May of this year, a rapid seasonal snowmelt accompanied by heavy rainfalls caused life-threatening raises of the level of water in rivers mostly affecting western and northern parts of the country. The disaster resulted in a death toll of at least seven people [kz.kursiv.media, 2024] while four people went missing [Kaz.nur.kz, 2024]. The flood resulted in significant economic losses, displacing over 200,000 people by inundating their homes. It caused critical damage to infrastructure, including roads and bridges, with estimated total losses, including the affected homes, of more than 200 billion tenge ($440 million) [Kaz.inform.kz, 2024].

The floods of the Spring of 2024 are often seen as part of a chain of disasters that took place in Kazakhstan over the past several years. For instance, in 2021, significant wildfires hit the central parts of Kazakhstan with substantial damage. The wildfire resulted in the death of one person and the loss of 200 heads of cattle. Due to severe drought conditions that year, the fire spread over a thousand hectares of land. The fire caused substantial economic losses by causing significant destruction to both property and farmlands, worsening the difficulties experienced by local farmers [Tengrinews.kz, 2024]. In September 2022, wildfires broke out in the Kostanay region, affecting about 9.4 thousand hectares of land and displacing around two thousand people. The fires caused significant environmental damage and disrupted the lives of many residents in the affected areas [Business-standard.com, 2024]. Heavy rainfall combined with warmer temperatures and melting snow led to widespread flooding again in April 2022. The disaster affected wide areas in regions of Mangystau, West Kazakhstan, Aktobe, Akmola, Karaganda, and Pavlodar, displacing 1,165 people and causing significant infrastructural damages. The alternation of droughts and floods continued intermittently hitting Kazakhstan through 2023 and 2024, acquiring an almost clear cyclical pattern and causing more economic losses from year to year.

There is evidence that the frequency of natural disasters in Kazakhstan has increased over the last several years. The total number of emergency situations and emergency situations caused by natural disasters in particular has been on the rise in Kazakhstan. Nearly three quarters of Kazakhstan’s territory is at high risk of natural disasters, and the frequency of these events has been increasing, leading to significant economic and human losses. In particular, Kazakhstan has faced regular and severe wildfires in the summer season. At the same time, the country has also experienced frequent spring floods due to rapid snowmelt and heavy rainfall during spring [UN News, 2024]. A clear increase in the frequency and intensity of natural disasters in Kazakhstan is driven by broader climatic changes and environmental factors and the continuation of this trend will continue producing various adverse effects and cost more to the economy. On the other hand, the patterns observed within the last 5-6 years can give us a rough understanding in which way the climate changes would manifest themselves in case of Kazakhstan, which can help to develop strategies of mitigation.

Thus, observations and studies from recent years already show that one of the most visible manifestations of climate change in Kazakhstan is the alterations in the patterns of snow cover in northern parts of Kazakhstan [Teleubay, 2022; Terekhov and Abayev, 2023]. Generally, observations over a longer period indicate a notable increase in heavy snowfall in northern regions and mountainous areas of Kazakhstan since the 1990s. This trend can be partially attributed to higher winter temperatures in winter, which increase atmospheric moisture and result in more intense snowfall events [ESCAP, 2021]. These changes also led to a significant increase in the frequency of mudslides in mountainous areas [The Economist, 2018], which is one of the risks for such densely populated areas as Almaty and adjacent areas. At the same time the frequency of wildfire and droughts increased over the years. Unfortunately, this trend is likely to continue in decades to come [Zong, et al., 2020].

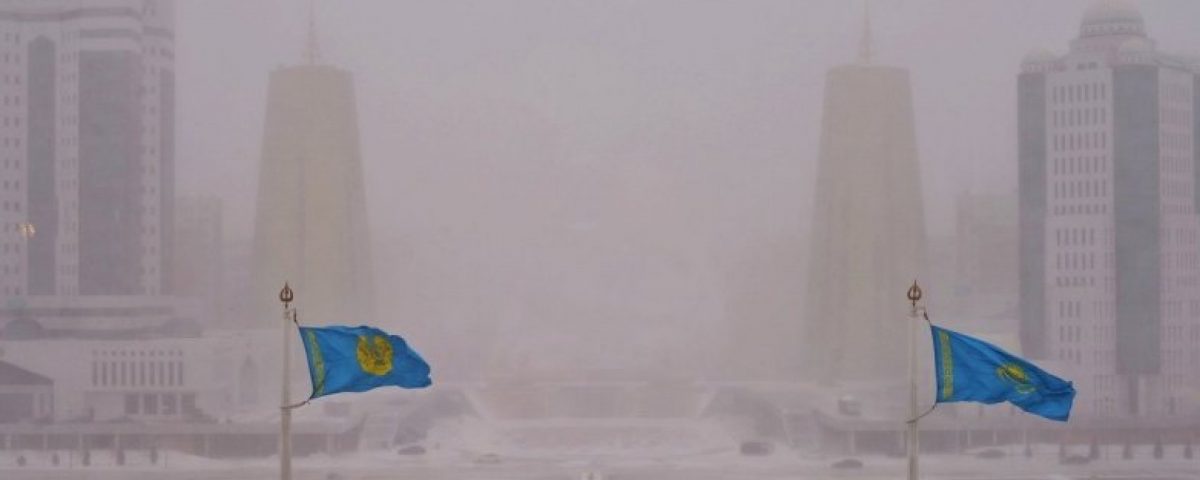

One of the issues that recent natural disasters have revealed is the poor and outdated state of infrastructure necessary to prevent the destructive consequences of such events. In particular, the lack of adequate river dams and canals to channel excess water became very evident during the floods of spring 2024. The recognition of this fact prompted the government of Kazakhstan to build 20 new reservoirs and reconstruct 15 existing ones in 11 regions of the country, which would significantly reduce the risk of flooding in 134 settlements across the country [Total.kz, 2024]. Similar to other post-Soviet countries, much of the infrastructure in Kazakhstan was built during the Soviet era. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan has faced economic difficulties, leading to insufficient maintenance and modernization of critical infrastructure such as dams, bridges, and flood control systems. This has left much of the infrastructure in a deteriorated state, unable to cope effectively with current and increasing disaster risks. Most importantly, there was no systematic approach to maintaining and renewing the technical standards of critical infrastructure meant to protect the population from natural disasters. The process of updating technical requirements and safety standards was often interrupted. Moreover, it might well be that even the construction of new infrastructure sometimes follows outdated standards, which are not capable of withstanding current risk exposures. This can be seen from the case of Astana, where we can see intermittent flooding caused each year by melting snow in spring seasons and heavy rains during summer over the past several years. The interesting fact is that the flooding occurs also in the newly built districts of the city where all urban infrastructure, including the water drainage system, is no older than 25 years old. Apparently, without a comprehensive approach to updating the technical requirements, the existing urban infrastructure of the city is incapable of withstanding the pressure of adverse weather events, especially under conditions of constant population growth. This can be extrapolated to other cities as well where the critical infrastructure designed to protect the city from natural disasters is outdated and not properly maintained.

Spatial demographics is another important consideration that has to be taken into account within the context of mitigation of natural disasters. Kazakhstan has seen a tremendous change in the patterns of its population distribution on territory. First of all, over the last 2-3 decades there has been a clear pattern of concentration of the population of Kazakhstan in several relatively small areas. Some areas of the country have seen huge demographic growth mainly due to internal migration while some other parts of the country were depopulated. This fact alone entails that there had to be an enlargement and significant readjustment of the disaster mitigation infrastructure. In particular, cities like Almaty, Astana and Shymkent currently are 2-4 times of the population size they had in early 1990s and are home to almost a quarter of the country’s population [Bureau of National Statistics, 2024]. The surrounding areas of these cities have also seen a major influx of internal migration, while the investments in disaster mitigation infrastructure around these cities have not been even remotely comparable. This issue became evident during the earthquakes that hit Almaty in January and March 2024. People were unable to locate designated evacuation areas, while others who attempted to evacuate themselves were stuck in huge traffic jams. It turns out that the rapid growth of these cities and the soaring demand for housing have been met with disregard for safety and disaster mitigation systems, which were not integral parts of the urban planning in these cities. Similarly, we can say that in many cases, the areas and settlements that have seen large demographic growth over the past 2-3 decades were hit particularly hard by the disaster. Towns and villages located around cities like Astana, Oral, Aktobe, Atyrau, and others have also grown rapidly in size over the past 2-3 decades and were severely affected. In other words, we can see a significant mismatch that has persisted for decades between local demographic factors and disaster mitigation systems and infrastructure.

A more generalized view helps us understand that the vast majority of issues related to natural disasters in Kazakhstan stem from systematic mismanagement and poor regional policies. Regardless of the type, scale, and severity of these disasters, one common feature persists: the lack of capacity among regional and local authorities to take quick measures. It is fair to say that, there are still issues with effective management to improve regional strategies, due to inheriting and preserving the over-centralized approach to territorial management from the USSR. The regions and local administrative units in Kazakhstan remain highly dependent on the central authorities. Interestingly, despite the active rearrangements of internal borders and changing the administrative statuses of some cities and regions, their degree of fiscal autonomy remains low especially in lower level constituencies. Limited fiscal autonomy and decision making capacity in centralized systems tend to limit local involvement and reduce the effectiveness of response efforts in case of emergency.

It is reasonable to expect that Kazakhstan would face a higher frequency of natural disasters in the near future, particularly driven by climate change. Kazakhstan, with its vast and varied terrain, is likely to experience more extreme temperatures, changes in precipitation patterns, and potentially more frequent droughts and floods [World Bank Group, 2021] as it is already being manifested. The risk of other disasters typical to the region also remains high. In this light, to mitigate the consequences of natural disasters, Kazakhstan should integrate disaster prevention into urban planning and regional development policies as integral components. Spatial demographics should be one of the key factors considered in building disaster mitigation infrastructure. As demonstrated by the practices of other countries, more autonomous and resourceful regions and local constituencies enhance their disaster resilience more effectively when they have greater autonomy and resources. Therefore, territorial decentralization is one of the key paths for Kazakhstan to build its capacity for mitigating natural disasters.

References:

Bureau of National Statistics (2024). Demographic statistics. Retrieved from https://stat.gov.kz/industries/social-statistics/demography/. Accessed on 14.06.2024.

Business-standard.com (2024). Wildfire scorches tens of thousands of acres in Kazakhstan; 2,000 displaced. Retrieved form https://www.business-standard.com/article/international/wildfire-scorches-tens-of-thousands-of-acres-in-kazakhstan-2-000-displaced-122090400056_1.html. Accessed on 11.06.2024.

ESCAP (2021). Kazakhstan – climate change and disaster risk profile. Retrieved form https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/event-documents/Kazakhstan%20-%20Climate%20Change%20and%20Disaster%20Risk%20Profile.pdf#:~:text=URL%3A%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.unescap.org%2Fsites%2Fdefault%2Fd8files%2Fevent. Accessed on 14.06.2024.

Kaz.inform.kz (2024). The loss of the flood may exceed 200 billion tenge – Yerlan Sairov’s prediction. Retrieved form https://kaz.inform.kz/news/taskinnin-shigini-200-mlrd-tengeden-asui-mumkn-erlan-sairovtin-bolzhami-3e4563/. Accessed on 14.06.2024.

Kaz.nur.kz (2024). Another person went missing during the flood in Abay region. Retrieved form https://kaz.nur.kz/society/2077106-abai-oblysynda-su-tasqyny-kezinde-tagy-bir-adam-zogalyp-ketti/. Accessed on 14.06.2024.

Kz.kursiv.media (2024). How many people died due to floods in Kazakhstan – the answer of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Retrieved form https://kz.kursiv.media/kk/2024-04-18/zmts-7-adam-koz-zhumdy/. Accessed on 11.06.2024.

Our World in Data (2024). Natural Disasters. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/natural-disasters. Accessed on 15.06.2024.

Salnikov, Vitaliy, Talanov, Yevgeniy, Polyakova, Svetlana, Assylbekova, Aizhan, Kauazov, Azamat, Bultekov, Nurken, Musralinova, Gulnur, Kissebayev, Daulet and Beldeubayev, Yerkebulan (2023). An assessment of the present trends in temperature and precipitation extremes in Kazakhstan. Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/2225-1154/11/2/33. Accessed on 15.06.2024.

Teleubay, Zhanassyl, Yermekov, Farabi, Tokbergenov, Ismail, Toleubekova, Zhanat, Igilmanov, Amangeldy, Yermekova, Zhadyra and Assylkhanova, Aigerim (2022). Comparison of snow indices in assessing snow cover depth in Northern Kazakhstan. Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/14/15/9643. Accessed on 16.06.2024.

Tengrinews.kz (2024). A man and hundreds of animals died in the steppe in the Karaganda region. Retrieved form https://tengrinews.kz/accidents/mujchina-sotni-jivotnyih-pogibli-stepi-karagandinskoy-442322/. Accessed on 14.06.2024.

Terekhov, Alexey and Abayev, Nurlan (2023). Changes in spatial distribution of snow deposit during 2001…2022 in East Kazakhstan. Gidrometeorologiya i ekologiya 2023 (1): 35-41.

The Economist (2018). Climate change poses significant risks to economy. Retrieved from http://country.eiu.com/article.aspx?articleid=576992241&Country=Kazakhstan&topic=Econo my. Accessed on 04.06.2024.

Total.kz (2024). Dozens of new dams will be built and reconstructed in Kazakhstan. Retrieved from https://total.kz/ru/news/vnutrennyaya_politika/desyatki_novih_damb_budut_postroeni_i_rekonstruirovani_v_kazahstane__tokaev_date_2024_04_25_12_03_15. Accessed on 14.06.2024.

United Nations News (2024). WMO report: Asia hit hardest by climate change and extreme weather. Retrieved form https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/04/1148886. Accessed on 14.06.2024.

United Nations Children’s Fund (2017). Disaster resilience. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/kazakhstan/en/disaster-resilience. Accessed on 15.06.2024.

World Bank Group (2021). Kazakhstan: Climate risk country profile.

Zong, Xuezheng, Tian, Xiaorui and Yin, Yunhe (2020). Impacts of climate change on wildfires in Central Asia. Forests, 11(802): 2-14.

Note: The views expressed in this blog are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the Institute’s editorial policy.