FILE PHOTO: A combine drives over stalks of soft red winter wheat during the harvest on a farm in Dixon, Illinois, July 16, 2013. REUTERS/Jim Young/File Photo/File Photo - RC1D7BDC5C00

Agriculture plays an important role in the global economy. Its functions are broad and include provision of food security, triggering of economic and industrial growth, poverty reduction, narrowing of income disparities, delivery of environmental services and structural transformations [Byerlee et al., 2009]. In the period of economic and political shocks, food security remains a major goal of any government. The recent pandemic shows an importance of trade in agricultural products for global food security, which increases the role and responsibility of food exporting countries. Wheat, which has a deep history in human civilization, remains one of the most important products in global trade. It is now the most widely cultivated cereal in the world. Its planted area exceeds 220 million hectares. Both developing and developed countries are involved in wheat production. The developing regions account for 53% of the total harvested area and 50% of the production. Wheat provides more than 35% of the cereal calorie intake in the developing world, 74% in the developed world and 41% globally from direct consumption. Almost 70% of wheat is used as food, while the shares of feed for livestock and industrial processing are 20% and 2–3%, respectively [Shiferaw et al., 2013].

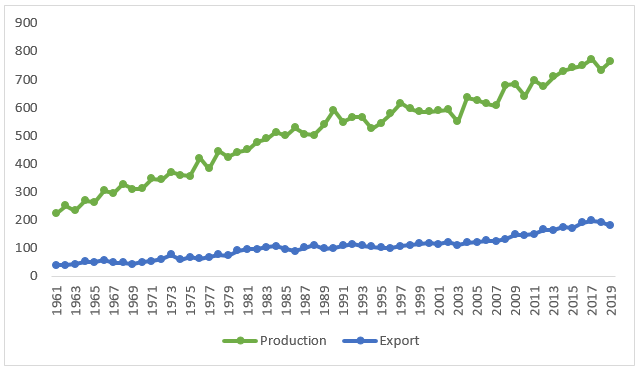

According to data from the International Grains Council (IGC, 2021), estimated production of wheat in 2019/2020 period was 763.7 million tons, of which more than 523.3 and 137.4 million tons were used for food and feed for livestock, respectively. The wheat volume for industrial processing equaled 24 million tons. Global export of wheat amounted to 184.3 million tons. The IGC forecasts that wheat production in 2020/2021 will reach 768 million tons, while consumption and export will increase to 531 and 186.8 million tons, respectively. Figure 1 shows trends in global production and export of wheat. According to data, in 1961 production and export of wheat amounted to 222 and 40 million tons, respectively. In 2019, production reached 766 million tons, increasing by 3.5 times. In the same year, export of wheat equaled 180 million tons growing by 4.5 times. Global trade in wheat increased substantially in value terms. While in 1961 global exports amounted to $2.5 billion, in 2019 it increased to $39.6 billion.

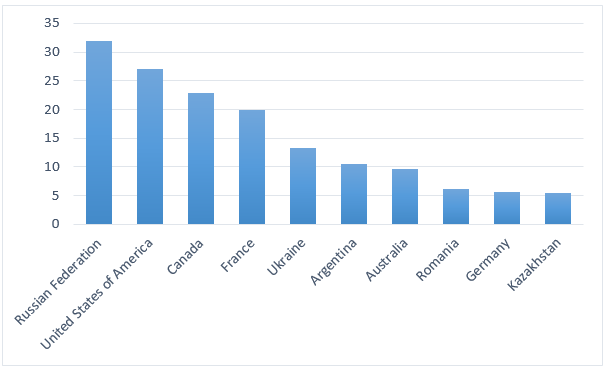

Figure 2 shows major exporters of wheat. Russia ranks first in the list of main wheat exporting countries. In 2019, its export equaled 32 million tons. The wheat supply of the United States amounted to 27 million tons, while Canada’s export reached 23 million tons.

Figure 1. Global production and export of wheat, million tons

Source: The Author’s compilation based on the FAOSTAT (2021) data

Figure 2. Major exporters of wheat, million tons

Source: The Author’s compilation based on the FAOSTAT (2021) data

Ukraine ranked fifth and in 2019 exported 13 million tons. Kazakhstan, in turn, supplied 5 million tons of wheat. In 2019, revenues of Russia from wheat export amounted to $6.4 billion. The United States and Canada exported wheat worth $6.3 and $5.4 billion, respectively. Ukraine and Kazakhstan, in turn, correspondingly earned $3.1 and $1 billion. This means that wheat export accounts for a significant share of the Eurasian countries’ non-mineral exports.

Therefore, the countries of the Eurasian region play an important role in global wheat exports. Various studies show the importance of Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan for the international grain markets and global food security. In particular, harvest in these countries or their policy towards regulation of grain markets have a significant impact on global markets. For instance, lower harvest or export restrictions or bans cause higher world prices. Higher prices are harmful for consumers but at the same time can be beneficial for producers. Increasing prices generally do not affect food security in high-income countries. However, economic costs for net grain importing lower-income countries are high despite their farmers may benefit from higher prices [Fellmann et al., 2014]. The recent pandemic disrupted global supply chains in many sectors, including agriculture. Despite production levels of wheat expected to be high, there is a concern that for political reasons, governments may respond to the uncertainty of the overall situation by limiting or banning wheat exports as well as by building up precautionary reserves. Such measures would affect global trade flows and would hurt all parts involved being counterproductive [Gutiérrez-Moya et al., 2020].

It should be noted that wheat dependence in low-income countries began after the Second World War and accelerated following the 1970s. However, the dependence on food imports does not necessarily mean food insecurity. At the same time, wheat dependence may well be a significant source of food insecurity, when combined with other variables, in particular income levels. Therefore, high wheat import dependency may be considered as a matter of food security in low‐income countries, as wheat‐based products account for a relatively high percentage of their total cereal consumption [González‐Esteban, 2018]. For instance, countries of Central Asia spend high shares of their income for food consumption. In Tajikistan, this portion amounts to 63%, and wheat, mainly in the form of bread, accounts for 40% to 60% of total daily food calories. As a result, growth in food prices lead to social and political unrest. For example, higher prices caused public protests in Uzbekistan in September 2007, in Tajikistan in February 2008 and in Kyrgyzstan in April 2010. Therefore, wheat self-sufficiency is crucial for the local governments. Local production in the majority of countries does not satisfy their internal demand. Consequently, on average, imports account for 41% of wheat consumption in Central Asia and Kazakhstan remains an exclusive supplier. Costs of wheat trade in the region are high due to high transportation costs and unofficial payments [Svanidze et al., 2019].

Wheat prices experienced significant changes. In December 1990, prices for metric ton of wheat were $113.2. In December 2000, they increased to $128. Since the early 2000-s the prices started to rise and peaked in March 2008, reaching almost $440. The global financial crisis and significant reduction of oil prices negatively affected the wheat prices. In September 2020, they equaled $198.4 [IndexMundi, 2021].

Majority of countries resisted agricultural trade liberalization and the sector was included only in the eighth round of multilateral trade negotiations, which is known as the Uruguay Round. A share of agriculture in global trade remains low but the sector is highly distorted. However, because of the relatively high levels of protection the sector accounts for almost 70% of the potential real income gains from trade reform. Therefore, economic costs of import tariffs and tariff-rate quotas remain significant [Laborde and Martin, 2012]. Understanding the importance of trade in agricultural products, many countries liberalized their trade policy. Despite agricultural tariffs remain highest, reduction in applied tariffs has been substantial. In particular, average agricultural tariff worldwide was reduced by 27.4% through multilateral, unilateral and regional concessions. It should be noted that applied agricultural protection is much lower than allowed by multilateral discipline within the World Trade Organization. Moreover, these reductions were driven mainly through self-imposed tariff reductions and regional trade agreements [Bureau et al., 2019].

Therefore, wheat plays a crucial role in many countries and provides a substantial share of daily calories. Both developing and developed countries produce wheat. As local production in the majority of countries do not satisfy internal needs, wheat import remains important for food security. Countries of the Eurasian region such as Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan play an important role in the global wheat market. Their decisions towards wheat export affect global prices and consumption. Higher prices for wheat products cause political unrest in many countries. Consequently, these countries and other wheat exporters should take into consideration economic and political implications of their decisions. It is important to note that countries started to liberalize their trade policy towards food products and achieved reduction of tariff and non-tariff barriers. This policy can lead to lower prices and improvement of their food security.

References:

Bureau, Jean-Christophe, Guimbard, Houssein and Sebastien Jean (2019). Agricultural Trade Liberalisation in the 21st Century: Has It Done the Business? Journal of Agricultural Economics, 70 (1): 3-25.

Byerlee, Derek, de Janvry, Alain, and Elisabeth Sadoulet (2009). Agriculture for Development: Toward a New Paradigm. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 1: 15–31.

FAOSTAT (2021). Production and Trade. Crops. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data. Accessed on 20.01.2021.

Fellmann, Thomas, Hélaine, Sophie and Olexandr Nekhay (2014). Harvest failures, temporary export restrictions and global food security: the example of limited grain exports from Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan. Food Security, 6: 727–742.

González‐Esteban, Ángel Luis (2018). Patterns of World Wheat Trade, 1945–2010: the Long Hangover from the Second Food Regime. Journal of Agrarian Change, 18 (1): 87–111.

Gutiérrez-Moya, Ester, Adenso-Díaz, Belarmino and Sebastián Lozano (2020). Analysis and vulnerability of the international wheat trade network. Food Security. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01117-9.

IndexMundi (2021). Wheat Monthly Price – US Dollars per Metric Ton. Retrieved from https://www.indexmundi.com/commodities/?commodity=wheat&months=360. Accessed on 20.01.2021.

International Grains Council (2021). Supply and Demand. Wheat. Retrieved from https://www.igc.int/en/markets/marketinfo-sd.aspx. Accessed on 23.01.2021.

Laborde, David and Will Martin (2012). Agricultural Trade: What Matters in the Doha Round? Annual Review of Resource Economics, 4: 265–160.

Shiferaw, Bekele, Smale, Melinda, Braun, Hans-Joachim, Duveiller, Etienne, Reynolds, Mathew and Geoffrey Muricho (2013). Crops that feed the world 10. Past successes and future challenges to the role played by wheat in global food security. Food Security, 5: 291–317.

Svanidze, Miranda, Götz, Linde, Djuric, Ivan and Thomas Glauben (2019). Food security and the functioning of wheat markets in Eurasia: a comparative price transmission analysis for the countries of Central Asia and the South Caucasus. Food Security, 11:733–752.

Note: The views expressed in this blog are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the Institute’s editorial policy.

Azimzhan Khitakhunov

Senior Research fellow

Azimzhan Khitakhunov is a research fellow at the Eurasian Research Institute. He has received his bachelor, master and Ph.D. degrees from Al-Farabi Kazakh National University (Ph.D. degree was completed in cooperation with the Johns Hopkins University, School of Advanced International Studies, Bologna, Italy). Currently, he is a senior lecturer at Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Higher School of Economics and Business, Economics Department, where he teaches macroeconomics related disciplines. His research experience includes participation as a research fellow in the government financed f